Home > Key Principles

Key Principles

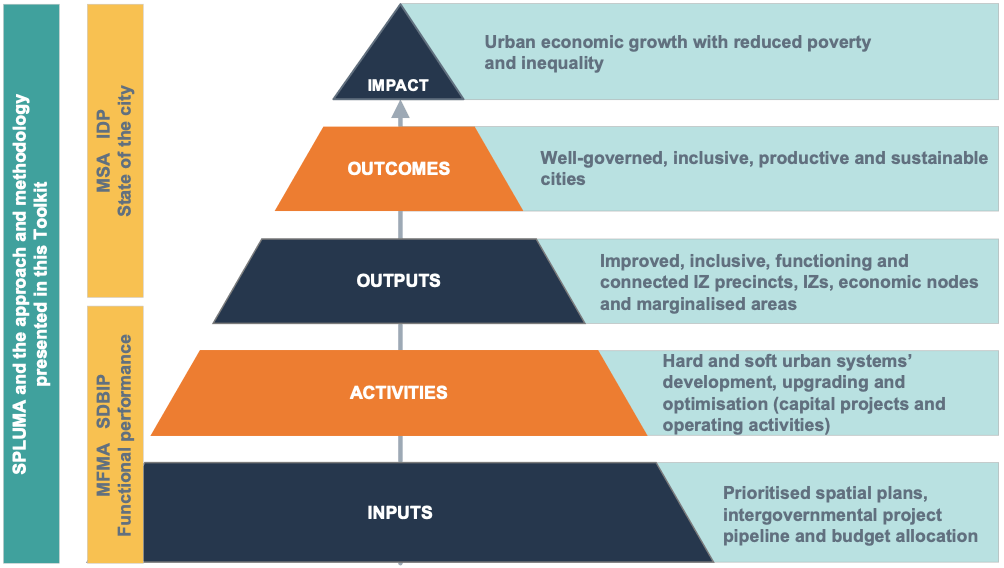

The approach, methodology and techniques presented in this Toolkit are supported of and consistent with the following two sets of principles:

- Spatial planning principles articulated in the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA); and

- Principles for spatial planning, implementation and urban management developed in response to the National Development Plan (NDP), the Integrated Urban Development Framework (IUDF), the Urban Network Strategy (UNS) and the BEPP process developed between National Treasury and metros.

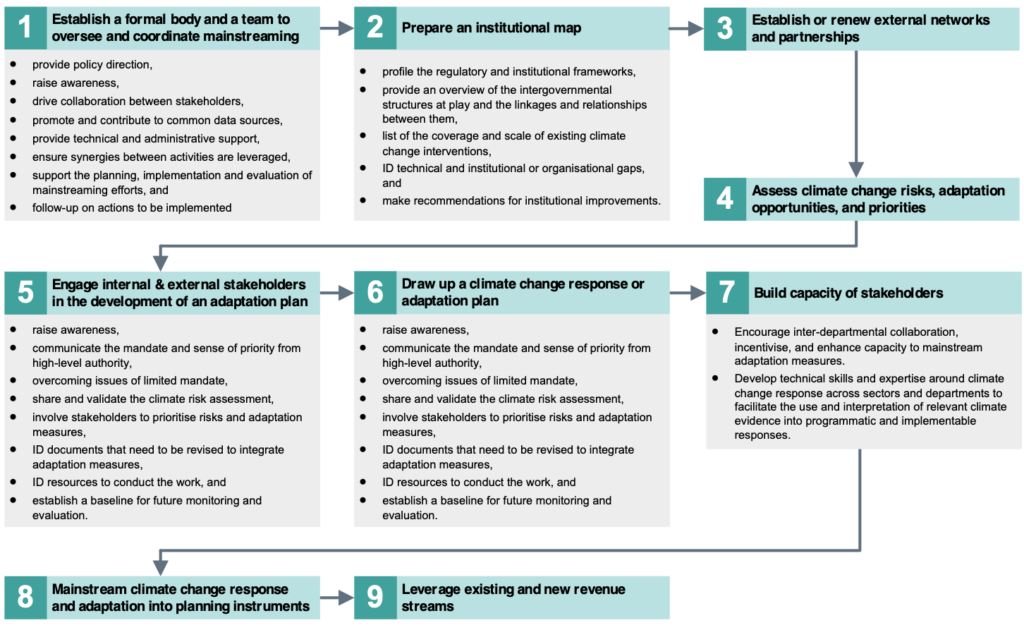

These 10 principles are – click on any principle to find out more:

Explore more on strategy and prioritised urban structuring elements